The wonderful novelist Jane Gardam, who wrote about working-class and aristocratic life Britain with precision and wit, died on Tuesday at the age of 96.

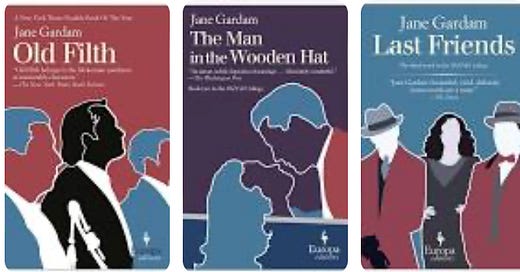

A few years ago, a friend gave me Old Filth, which came out in 2004 and is generally considered her masterpiece. I loved it, and in quick succession read The Man in the Wooden Hat, Bilgewater, and a 500-page volume of her extraordinary stories.

Gardam was what some might call a late bloomer: she didn’t start writing until the youngest of her three children went to preschool. But on the very morning he left, she put pen to paper, and for the rest of her life she hardly stopped. She published her first book at 43; Old Filth came out when she was 76. She won the Whitbread twice and was awarded an OBE for services to literature.

Gardam always wrote by hand; she found it quicker that way. “I think my schoolmaster’s family taught me to sit down at a desk and, you know, work,” she told the Paris Review in 2022. Ideas for short stories came easily to her—whenever, she said, “someone says, Jane, we need a short story.” (I’m not grinding my teeth in envy, you are.)

Her books, she said, “were true and yet they were not specifically true.” The career of her barrister husband partly inspired Old Filth, a tragicomedy about a retired judge grieving the death of his wife. The Queen of the Tambourine, set in the Wimbledon neighborhood where Gardam raised her children, focused on “rich suburban women who are very intelligent and don’t have enough to do.”

But the ultimate subject of her books, Gardam says, was “the end of empire.” (Even if, as she said in a different interview, “We never know what the hell we’re writing about, not even when the book’s over.”)

For Gardam, writing was about “getting to know a character and loving them.” And it was an act essential to life: “It was just what I had to do. It seemed the only way to live to me, to be happy.”

For today’s writing prompt, let’s take a look at scene in the second chapter of God on the Rocks (I just started this yesterday), in which precocious, prickly eight-year-old Margaret comes into the house while her mother is nursing Margaret’s new baby brother. As Mrs. March blissfully tends to her beautiful “little lovekin,” Margaret observes with deep and comical disgust.

[Margaret’s mother] lifted the baby up on her shoulder where a huge towelling nappy lay, hanging a little way down her back for the baby to be sick on. She massaged its back, which was like the back of a duck, oven-ready. The baby’s unsteady head and swivelling eyes rolled on her shoulder, its round mouth slightly open, wet and red. It seemed, filmily, to be trying to take in Margaret, who was fiddling with things on the mantelpiece behind her mother. She looked down at it with a realistic glare. The baby under the massage let air come out of its mouth in a long explosion and pale milk ran out and over its chin.

“Filthy,” said Margaret.

Lol! A few minutes later, when Mrs. March suggest that the baby will love Margaret, Margaret declares that she doesn’t care. The world would be better off without any people at all; God, she says, should’ve quit after the dinosaurs and called it good.

When her mother gently points out that this is blasphemy, Margaret asks what this is.

“Margaret! Blasphemy is taking the name of God in vain.”

“In vain. A lot of things are in vain.”

“No. It means lightly. You are taking the name of God lightly.”

“Better than heavily."

“God,” said Mrs. Marsh, going rather red in the cheeks and buttoning her dress after adjusting a massive camisole beneath and easing herself to an even balance, “made us in his own image.” She looked at the trussed baby, face down, its red head like a tilted orange rearing up and down on the undersheet as if desperately attempting to escape. Giving up, it let its head drop into suffocation position and there was another explosion followed by a long, liquid spluttering from further down the cot: and a smell. “Oh dear,” said Mrs Marsh contented, “now I'll have to start all over again with a new nappy. Could you hand me the bucket, darling?”

“His own image,” said Margaret watching the horrible unwrapping. “If God looks like us ….. What’s the point?”

“You must speak,” said Mrs. Marsh sternly, “to your father.”

And now, for your writing prompt:

Write a scene in which two people observe the same thing (be it a person, an interaction, a work of art, or anything at all) and have entirely different opinions about it. Bonus points for crackling dialogue. (Gardam’s a genius at this, though I’m not sure these brief excerpts prove it.)

Happy writing—

Emily

“A long, liquid sputtering”! Love this.